|

In

1938 the residents of Dundonald took on the might of the Belfast & County

Down Railway Company in a dispute over the right of way across “Quarry Lane

Stile”.

The

picture below was taken at the time.

It is looking down the newly created Grand Prix Park towards Dundonald

village. The school is directly ahead in the distance. You can see at this time

houses are beginning to be built. Problems arose when people, especially

those living on the “wrong side” of the tracks started to use this crossing for

access.

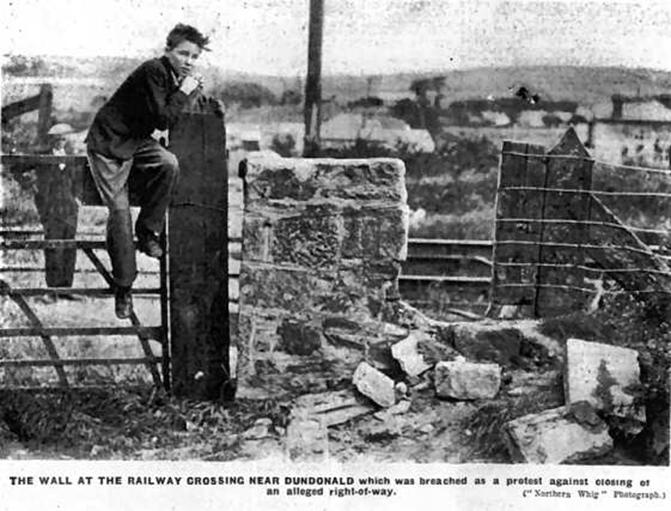

This Photograph was taken by

famous Belfast

photographer Alexander Hogg 1870-1939. It is dated 2nd July 1938

which was in the middle of the “crossing dispute”. The demolished remains of

the blocked up stile can be seen to the right of the gate. It is likely that

the B&CDR company commissioned Hogg to record this photographic evidence

to support their case in court. Please note that this photograph has been

reproduced with the permission of National

Museums Northern Ireland and

may not be downloaded, copied or reproduced in any form without their consent.

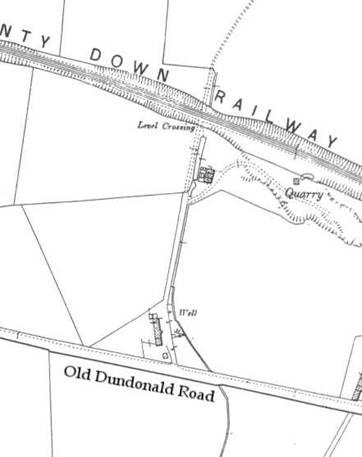

The

map left shows the crossing in 1902. (The station is about 500 ft the right

of the quarry). The

map left shows the crossing in 1902. (The station is about 500 ft the right

of the quarry).

This

shows that Quarry Lane Crossing was built as an ordinary farm accommodation

crossing. It was originally put in place in 1850 for the owner of the land

severed by the railway as it wended its way from Knock to Dundonald. The

crossing was known at the time as

“McKenzie’s accommodation crossing”. The landowner had a legal right of way

across the railway and held keys for the gates at the crossing.

The

crossing was situated at the end of a laneway which ran from a farm on the

Old Dundonald Road to a Quarry and some Workmen’s cottages near the Railway.

On the other side of the railway a footpath ran down to the Comber Road, and

then up to the school, churches and centre of Dundonald village.

The

crossing itself consisted of two farm gates, one on either side of the

tracks. The gates were in the distinctive rising sun design used by the Company.

Beside the gates were two stone stiles, one on either side of the line.

During

the years between the wars, the population of Dundonald doubled. Many of the newcomers were ‘townies’ from the ever expanding city of

Belfast. By 1937 the population numbered 1,664. Many new houses were built to

accommodate the rising demand. The railway encouraged growth in the south of

the parish. Middle-class villas were built along the Old Dundonald and Comber

Roads, whilst less grand dwellings of tin and wood sprang up on Quarry Lane

and the Gransha Road. The areas locally becoming known as ‘Tin Town’ and

‘Timber Town’ respectively.

At

this time a new development of

villas was built around a road centred on the old path from Quarry Lane

crossing to the Comber Road. This was named ‘Grand Prix Park’ in honour of

the annual T.T. race, of which the Comber Road formed part of the course.

For

people living south of the Railway there were two routes for crossing the

railway lines to get to the village. The first was to go via the road bridge at

the station. The second and more direct route for many was to go down Quarry

Lane, across the tracks and down Grand Prix Park. As more and more people

used the crossing the Railway Company began to take notice.

On 1st

June 1938, the General Manager, Mr. W. F. Minnis reported to the Board:

“Quite

recently a new road named Grand Prix Park, has been constructed from the main

Comber Road up to the Railway Crossing on which quite a number of villas have

been erected, with the result that the accommodation crossing is now being

used by a number of residents on both sides of the line.”

The

Board ever mindful of the risk of legal action arising from an accident

agreed that the stiles at the crossing should be removed “in order to

counteract any suggestion that their being there was an invitation to the

public to make use of the Crossing.” This was in accordance with legal advice

given to the Company in 1923 that all such stiles should be removed.

The

fact of the matter however was that the route down Quarry Lane and Grand Prix

Park offered a substantial short cut for many living south of the railway, if

they wished to go to the village (a short cut which is still used by locals

to this day). We must remember that motor cars were not in such abundance as

today and most people had to walk to attend school, to visit the shops or to

worship at their church.

The

Company Engineer arranged for the stiles to be built up. If necessary, keys

for the gates would be supplied to the residents of the workmen’s cottages

adjacent to the crossing, though only if they could prove they had right of

way to cross the railway. The local residents didn’t take this move lying

down! No sooner had the stiles been blocked up than some firebrand residents

knocked the work down again. The company blocked them up again, and again the

work was knocked down. This continued for four consecutive days from the 22nd

June to 25th June.

This

photograph reproduced from the Weekly Northern Whig Newspaper June 1938 shows

the crossing from the Quarry Lane side looking across the railway towards

Grand Prix Park and Dundonald Village. The rubble from the demolished attempt

to block up the stile can be seen strewn about the ground.

The

final demolition occurred on the 25th June prior to a protest meeting

which was attended by over 100 people. They assembled on either side of the

line where they were separated by the stone and earth walls built up by the

Company. Using a plank of wood as a battering ram, some of the men in the

crowd knocked down the walls. With the way cleared, the crowd merged for the

meeting at the top of Grand Prix Park.

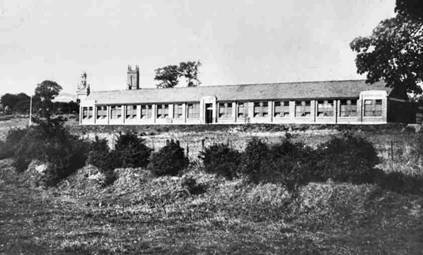

Stanley

Wright the principal of Dundonald Public Elementary School addressed the

crowd. He stated that 65 school children used the crossing everyday and that

since the way had been barred school attendance had been affected. Perhaps it

was more a case of any excuse for a day off school! The photograph to the

right shows the ‘new school’ built in 1923. A path led to the school from the

Comber Road directly opposite grand Prix Park. Stanley

Wright the principal of Dundonald Public Elementary School addressed the

crowd. He stated that 65 school children used the crossing everyday and that

since the way had been barred school attendance had been affected. Perhaps it

was more a case of any excuse for a day off school! The photograph to the

right shows the ‘new school’ built in 1923. A path led to the school from the

Comber Road directly opposite grand Prix Park.

The

police also attended the scene but did not interfere, seeing the matter as

one for resolution by the residents and the Railway Company. A petition to

Mr. Andrews, Minister of Finance, M.P. for the area and BCDR Director, was

signed on behalf of the local Presbyterian Church, Church of

Ireland, Methodist Church and

by the people of the district.

The

result was that the place was left quite open and the Company felt obliged to

post Watchmen until the matter could be resolved. At first they turned to the

Police. They, however, were completely uninterested in getting involved,

stating it was a matter for agreement between the residents and the Company.

Perhaps it was that the local constabulary had some sympathy for the

residents’ case. Not to be deterred, the Company turned to the law. The

Company’s solicitors Messrs. E & R. D. Bates advised application for an

Interlocutory injunction to restrain the local inhabitants from “further

interference with the Company’s property”. This was to be pursued against the

six men who the Company believed had done the damage.

The

residents of Dundonald responded with a deputation to the General Manager.

This consisted of the Rev. James McQuitty (Presbyterian), Rev. John Cotter (Church

of Ireland), Messrs. Bossence, Fullerton (Methodist minister), J. W. Porter

and Stanley Wright (Primary school principal). These gentlemen were anxious

that something be done to provide a footbridge. The Company, however,

continued to pursue its legal action.

The case came before Mr Justice

Megaw at the Chancery Court of the Royal Courts of Justice at 11 a.m. on

Wednesday 22nd March 1939. (Picture courtesy of St. Andrews

University Library). The Company’s injunction was not defended as the six men

in question had no means of meeting the legal expenses. The Courts granted

the Company’s injunction and awarded costs against the defendants, William

Jamison, labourer, Old Dundonald Road; William Collins, labourer, Wilmar,

Quarry Lane; Andrew Walsh, electric welder, Quarry Lane; William McGuffin,

electrician, Quarry Lane; Ernest Martin, labourer, Hill Crest, Old Dundonald

Road, and Thomas Moore Sen., labourer, Quarry Lane, Ballybeen, Dundonald. No

compensation was applied for or allowed. The Company decided not to pursue

the matter of costs as the defendants were all working men and there appeared

to be no prospect of their being able to pay. Mr. Justice Megaw said the

crossing had been used by a great many members of the public by reason of the

non-interference of the Company. It was, no doubt, a great convenience.

Overhead or underground accommodation would be of value, but the Company did

not feel justified in incurring the expenditure. The stiles were again built

up and the Watchmen withdrawn from the area. The case came before Mr Justice

Megaw at the Chancery Court of the Royal Courts of Justice at 11 a.m. on

Wednesday 22nd March 1939. (Picture courtesy of St. Andrews

University Library). The Company’s injunction was not defended as the six men

in question had no means of meeting the legal expenses. The Courts granted

the Company’s injunction and awarded costs against the defendants, William

Jamison, labourer, Old Dundonald Road; William Collins, labourer, Wilmar,

Quarry Lane; Andrew Walsh, electric welder, Quarry Lane; William McGuffin,

electrician, Quarry Lane; Ernest Martin, labourer, Hill Crest, Old Dundonald

Road, and Thomas Moore Sen., labourer, Quarry Lane, Ballybeen, Dundonald. No

compensation was applied for or allowed. The Company decided not to pursue

the matter of costs as the defendants were all working men and there appeared

to be no prospect of their being able to pay. Mr. Justice Megaw said the

crossing had been used by a great many members of the public by reason of the

non-interference of the Company. It was, no doubt, a great convenience.

Overhead or underground accommodation would be of value, but the Company did

not feel justified in incurring the expenditure. The stiles were again built

up and the Watchmen withdrawn from the area.

After

the court case the Board considered closing all stiles at accommodation

crossings to avoid any further trouble like that which had taken place at

Dundonald. In 1939, it was estimated

that there were approximately 104 stiles at level crossings on the system. It

seems, however, that this action was not acted upon, the Board preferring to

deal with these matters on a case by case basis.

The

residents formed the “Dundonald Right of Way Association” and continued to

lobby for passage across the railway tracks at Quarry Lane. They asked the

Company if they would be prepared to dispose of the metal Footbridge at

Tillysburn and move it to Quarry Lane. This Halt had been closed since 1931

and the bridge was unused. This, however, never came to pass and it can only

be assumed the costs involved proved to be too high and the matter was

abandoned. Soon the nation was to be plunged into war and minds no doubt were

occupied by more important matters.

Wartime

traffic saw the re-opening of Tillysburn in 1941 until its final closure in

1945. The bridge was eventually moved, not to Dundonald but to Mount Halt on

the Larne Line by the UTA. The residents of Dundonald would have to wait

until 1950 and the closure of the County Down railway before free passage was

once again available down Quarry

Lane onto Grand Prix Park.

The view down Grand Prix

Park in 2013. The Comber Greenway has replaced the railway; pedestrians most

welcome!

|